User-generated graphics in the browser with SVG

The challenge

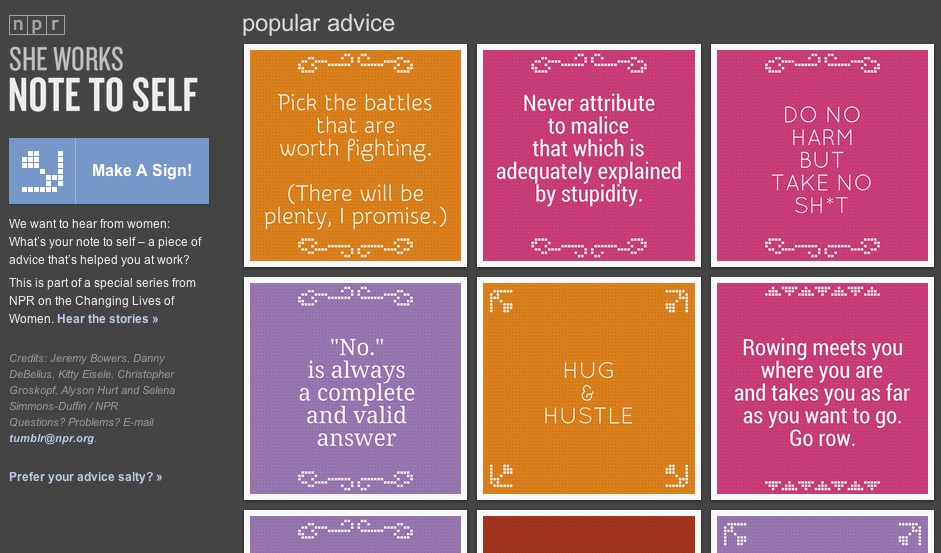

For NPR’s ongoing series “The Changing Lives of Women”, we wanted to ask women to share advice gleaned from their experience in the workforce. We’ve done a few user-generated content projects using Tumblr as a backend, most notably Cook Your Cupboard, so we knew we wanted to reuse that infrastructure. Tumblr provides a very natural format for displaying images as well as baked in tools for sharing and content management. For Cook your Cupboard we had users submit photos, but for this project we couldn’t think of a photo to ask our users to take that would say something meaningful about their workplace experience. So, with the help of our friends at Morning Edition, we arrived at the idea of a sign generator and our question:

“What’s your note to self – a piece of advice that’s helped you at work?”

With that in mind we sketched up a user interface that gave users some ability to customize their submission—font, color, etc—but also guaranteed us a certain amount of visual and thematic consistency.

Making images online

The traditional way of generating images in the browser is to use Flash, which is what sites like quickmeme do. We certainly weren’t going to do that. All of our apps must work across all major browsers and on mobile devices. My initial instinct said we could solve this problem with the HTML5 Canvas element. Some folks already use Canvas for resizing images on mobile devices before uploading them, so it seemed like a natural fit. However, in addition to saving the images to Tumblr, we also wanted to generate a very high-resolution version for printing. Generating this on the client would have made for large file sizes at upload time—a deal-breaker for mobile devices. Scaling it up on the server would have lead to poor quality for printing.

After some deliberation I fell upon the idea of using Raphaël.js to generate SVG in the browser. SVG stands for Scalable Vector Graphics, an image format typically used for icons, logos and other graphics that need to be rendered at a variety of sizes. SVG, like HTML, is based on XML and in modern browsers you can embed SVG content directly into your HTML. This also means that you can use standard DOM manipulation tools to modify SVG elements directly in the browser. (And also style them dynamically, as you can see in our recent Arrested Development visualization.)

The first prototype of this strategy came together remarkably quickly. The user selects text, colors and ornamentation. These are rendered as SVG elements directly into the page DOM. Upon hitting submit, we grab the text of the SVG using jQuery’s html method and then assign to a hidden input in the form:

The SVG graphic is sent to the server as text via the hidden form field. We’ve already been running servers for our Tumblr projects to construct the post content and add tags before submitting to Tumblr, so we didn’t have to create any new infrastructure for this. (Tumblr also provides a form for having users submit directly, which we are not using for a variety of reasons.) You can see our boilerplate for building projects with Tumblr on the init-tumblr branch of our app-template.

Once the SVG text is on the server we save it to a file and use cairosvg to cut a PNG, which we then POST to Tumblr. Tumblr returns a URL to the new “blog post”, which we then send to the user as a 301 redirect. To the user it appears as though they posted their image directly to Tumblr.

Problems

Text

Text was probably the hardest thing to get right. Because each browser renders text in a different way we found that our resulting images were inconsistent and often ugly. Worse yet, because our server-side, Cairo-based renderer was also different, we couldn’t guarantee the text layout a user saw on their screen would match that of the final image once we’d converted it to a PNG.

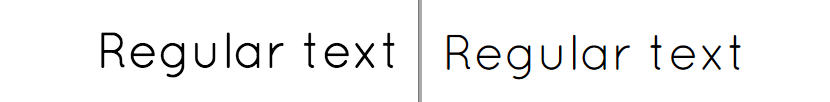

Here is the same text (Quicksand 400), rendered in Chrome on the left and IE9 on the right:

Researching a solution for this led me to discover Cufon fonts, a JSON format for representing fonts as SVG paths (technically VML paths, but that doesn’t matter). There is a Cufon Javascript library for using these fonts directly, however, there are also built-in hooks for using them Raphaël. (For those who care: they get loaded up via a “magic” callback name.) These resulting fonts are ideal for us, because the paths are already set and thus look the same in every browser and when rendered on the server. It’s a beautiful thing:

Scaling

We found that the various SVG implementations we had to work with (Webkit, IE, Cairo) had different interpretations of width, height and viewBox parameters of the SVG. We ended up using a fixed size for viewBox (2048x2048) and rendering everything in that coordinate reference system. The width and height we scaled with our responsive viewport. On the server width and height were stripped before the SVG was sent to cairosvg, causing it to render the resulting PNGs at viewBox size. See the next section for the code that cleans up the SVG on the server.

Browser support

A similar issue happened with IE9, which for no apparent reason was duplicating the XML namespace attribute of the SVG, xmlns. This caused cairosvg to bomb, so we had to strip it.

Unfortunately, no amount of clever rewriting was ever going to make this work in IE8, which does not support SVG. Note that Raphaël does support IE8, by rendering VML instead of SVG, however, we have no way to get the XML text of the VML from the browser. (And even if we could we would then have to figure out how to convert the VML to a PNG in a way that precisely matched the output from our SVG process.)

Here is the code we use to normalize the SVGs before passing them to cairosvg:

Glyphs

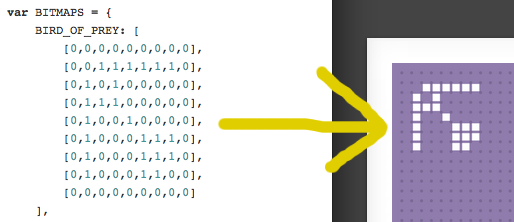

One final thing we did for this project that is worth mentioning is building out a lightweight system for defining the ornaments you that can be selected as decoration for your quote. Although there is nothing technically challenging about this (it’s a grid of squares), it was awfully fun code to write:

And it gave us a chance to use good-old-fashioned bitmaps for the configuration:

You can see the full ornament definitions in this gist.

Conclusion

By using SVG to generate images we were able to produce user-generated images suitable for printing at large size in a cross-platform and mobile-friendly way. It also provided us an opportunity to be playful and explore some interesting new image composition techniques. This “sign generator” approach seems to have resonated with users and resulted in over 1,100 submissions!

visuals + editorial graphics

visuals + editorial graphics