How We Built Borderland Out Of A Spreadsheet

Since the NPR News Apps team merged with the Multimedia team, now known as the Visuals team, we’ve been working on different types of projects. Planet Money Makes a T-Shirt was the first real “Visuals” project, and since then, we’ve been telling more stories that are driven by photos and video such as Wolves at the Door and Grave Science. Borderland is the most recent visual story we have built, and its size and breadth required us to develop a smart process for handling a huge variety of content.

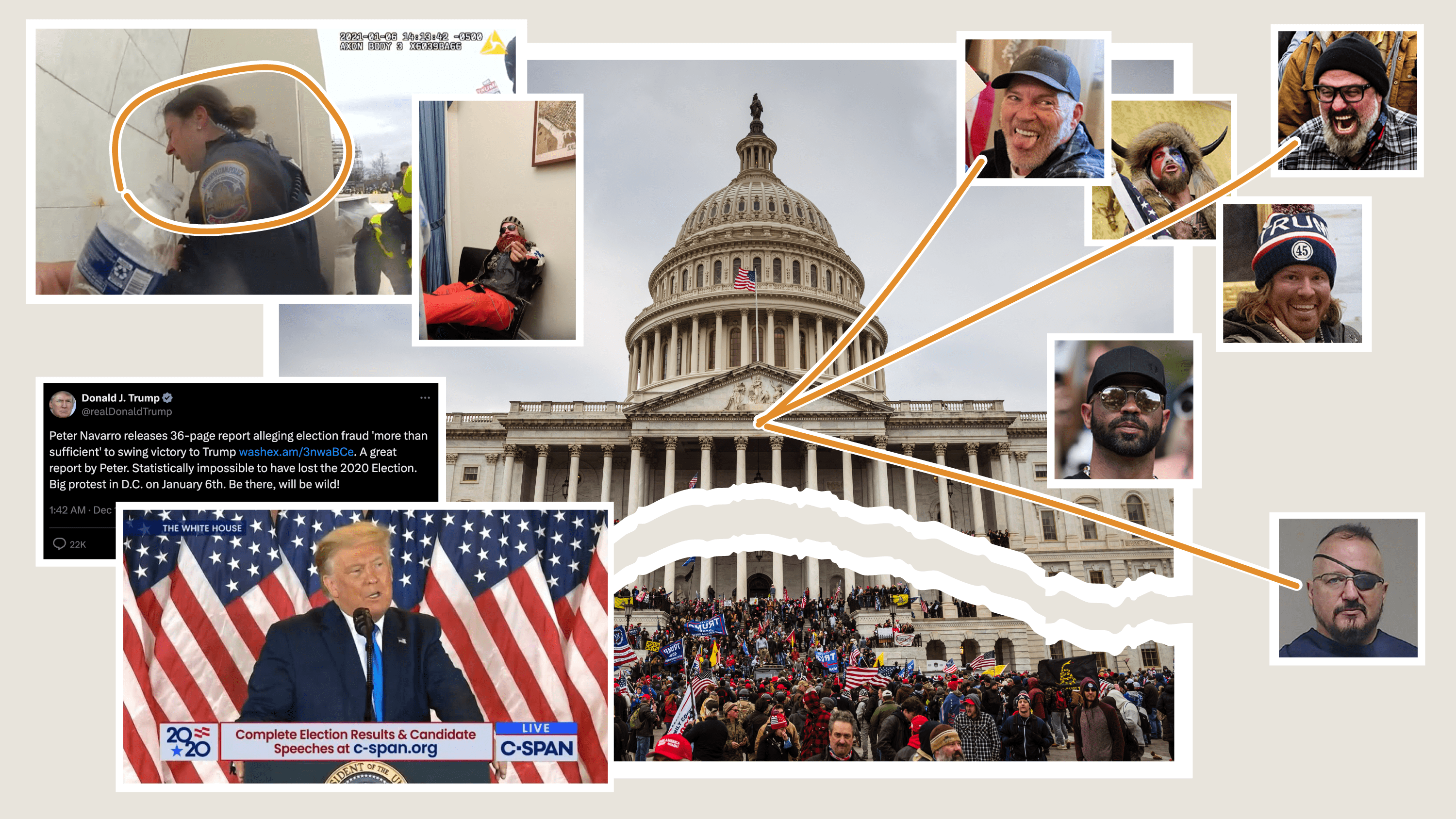

Borderland is a giant slide deck. 129 slides, to be exact. Within those slides, we tell 12 independent stories about the U.S.-Mexico border. Some of these stories are told in photos, some are told in text, some are told in maps and some are told in video. Managing all of this varying content coming from writers, photographers, editors and cartographers was a challenge, and one that made editing an HTML file directly impossible. Instead, we used a spreadsheet to manage all of our content.

On Monday, the team released copytext.py, a Python library for accessing spreadsheets as native Python objects so that they can be used for templating. Copytext, paired with our Flask-driven app template, allows us to use Google Spreadsheets as a lightweight CMS. You can read the fine details about how we set that up in the Flask app here, but for now, know that we have a global COPY object accessible to our templates that is filled with the data from a Google Spreadsheet.

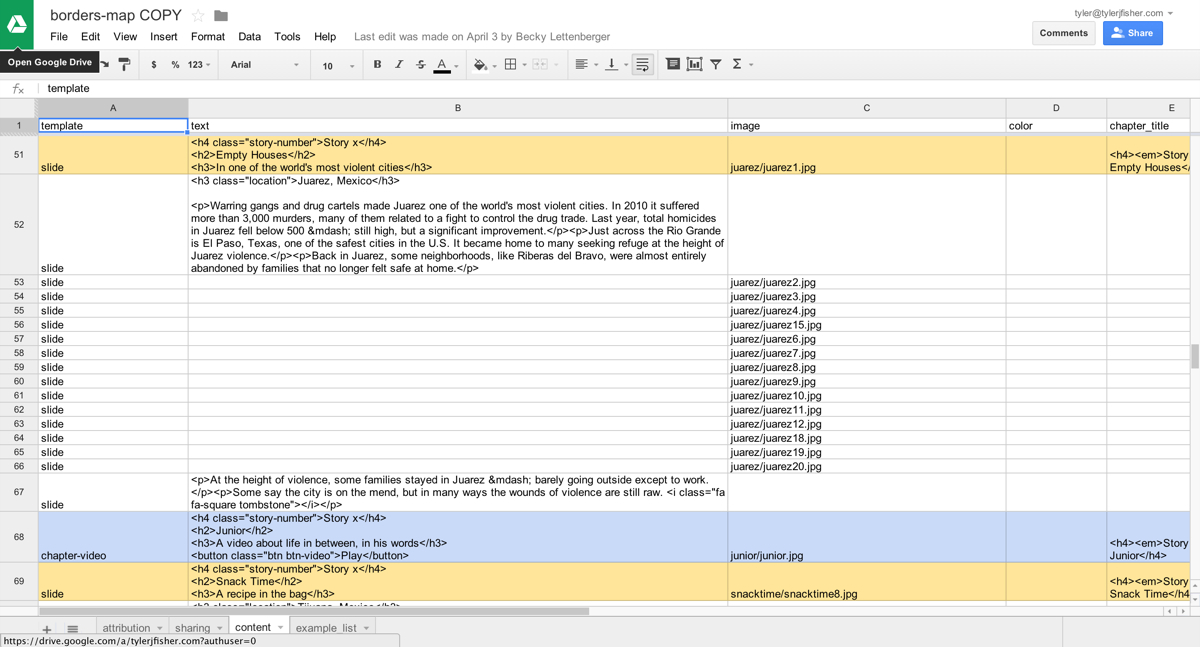

In the Google Spreadsheet project, we can create multiple sheets. For Borderland, our most important sheet was the content sheet, shown above. Within that sheet lived all of the text, images, background colors and more. The most important column in that sheet, however, is the first one, called template. The template column is filled with the name of a corresponding Jinja2 template we create in our project repo. For example, a row where the template column has a value of “slide” will be rendered with the “slide.html” template.

We do this with some simple looping in our index.html file:

In this loop, we search for a template matching the value of each row’s template column. If we find one, we render the row’s content through that template. If it is not found (for example, in the first row of the spreadsheet, where we set column headers), then we skip the row thanks to ignore missing. We can access all of that row’s content and render the content in any way we like.

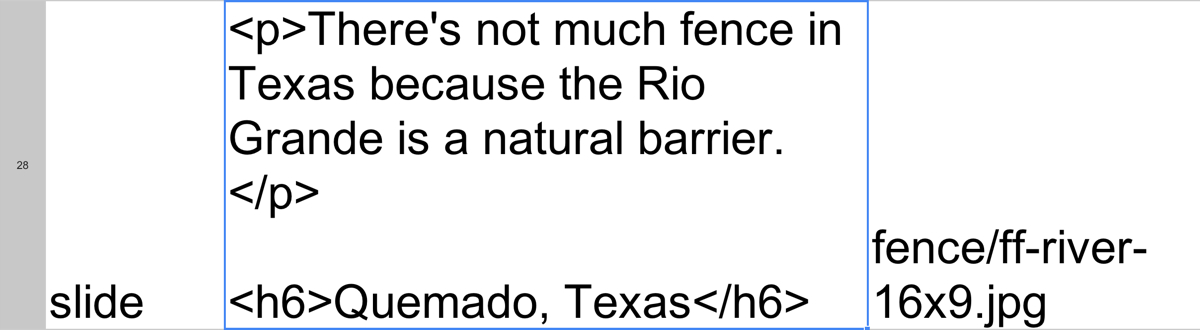

Let’s look at a specific example. Here’s row 28 of our spreadsheet.

It is given the slide template, and has both text and an image associated with it. Jinja recognizes this template slug and passes the row to the slide.html template.

There’s a lot going on here, but note that the text column is placed within the full-block-content div, and the image is set in the data-bgimage attribute in the container div, which we use for lazy-loading our assets at the correct time.

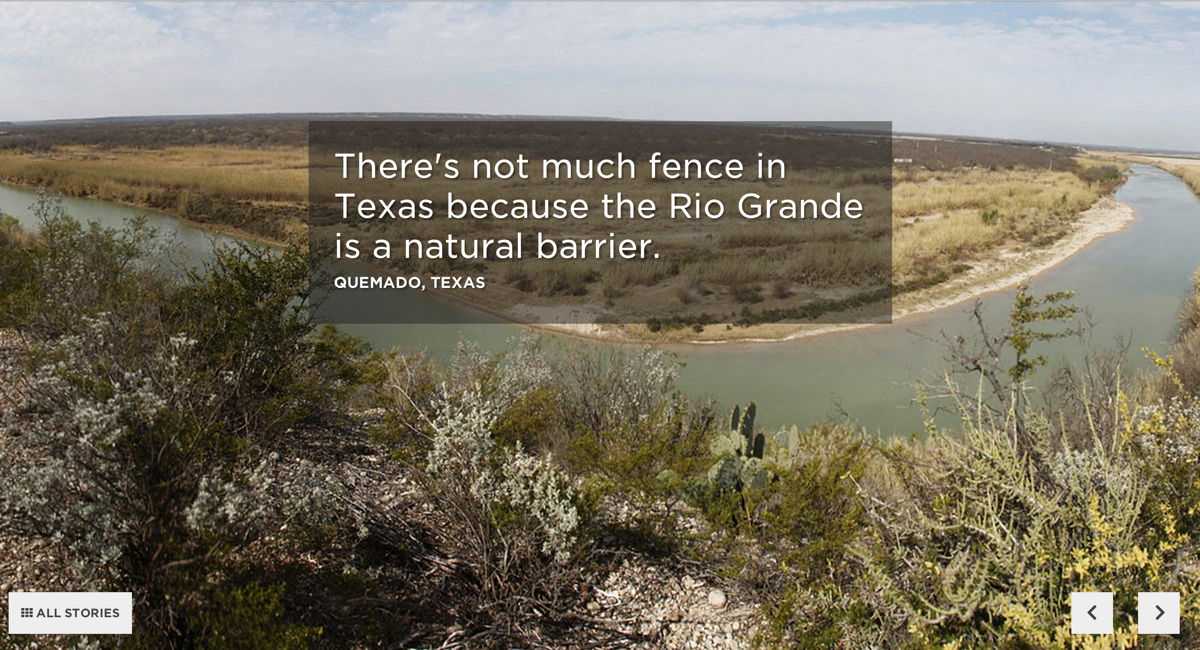

The result is slide 25:

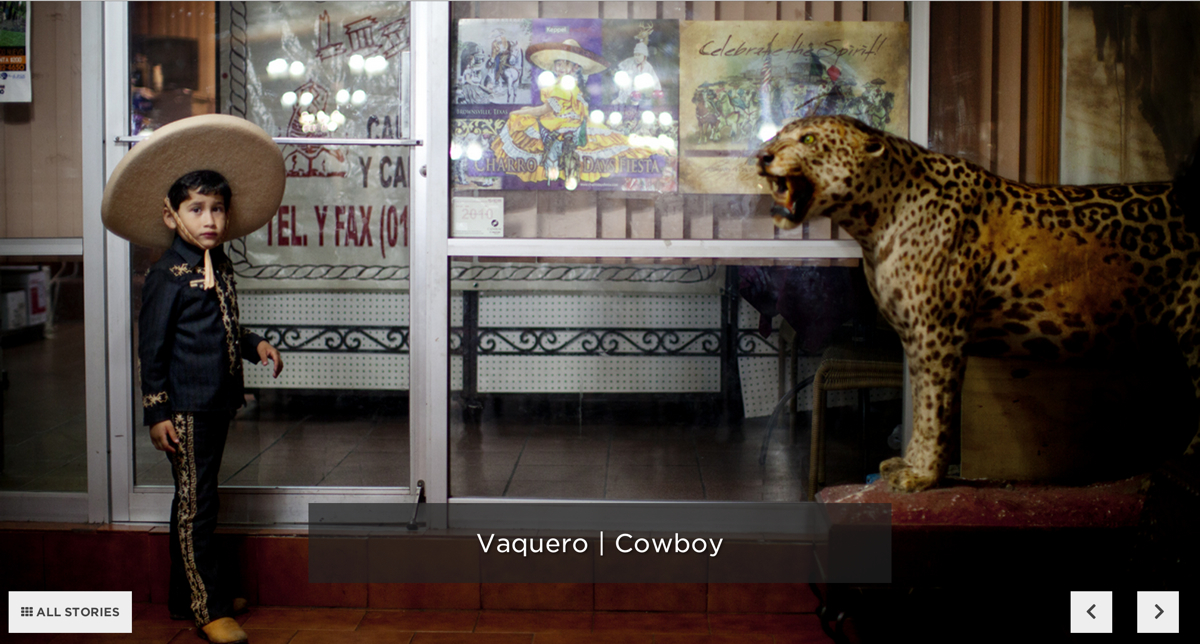

Looping through each row of our spreadsheet like this is extremely powerful. It allow us to create arbitrary reusable templates for each of our projects. In Borderland, the vast majority of our rows were slide templates. However, the “What’s It Like” section of the project required a different treatment in the template markup to retain both readability of the quotations and visibiilty of the images. So we created a new template, called slide-big-quote to deal with those issues.

Other times, we didn’t need to alter the markup; we just needed to style particular aspects of a slide differently. That’s why we have an extra_class column that allows us to tie classes to particular rows and style them properly in our LESS file. For example, we gave many slides within the “Words” section the class word-pair to handle the treatment of the text in this section. Rather than write a whole new template, we wrote a little bit of LESS to handle the treatment.

More importantly, the spreadsheet separated concerns among our team well. Content producers never had to do more than write some rudimentary HTML for each slide in the cell of the spreadsheet, allowing them to focus on editorial voice and flow. Meanwhile, the developers and designers could focus on the templating and functionality as the content evolved in the spreadsheet. We were able to iterate quickly and play with many different treatments of our content before settling on the final product.

Using a spreadsheet as a lightweight CMS is certainly an imperfect solution to a difficult problem. Writing multiple lines of HTML in a spreadsheet cell is an unfriendly interface, and relying on Google to synchronize our content seems tenuous at best (though we do create a local .xlsx file with a Fabric command instead of relying on Google for development). But for us, this solution makes the most sense. By making our content modular and templatable, we can iterate over design solutions quickly and effectively and allow our content producers to be directly involved in the process of storytelling on the web.

Does this solution sound like something that appeals to you? Check out our app template to see the full rig, or check out copytext.py if you want to template with spreadsheets in Python.

visuals + editorial graphics

visuals + editorial graphics