How we approached data cleaning for our listeners' favorite albums of 2017

All Songs Considered asks listeners for their favorite albums of 2017

All Songs Considered asks listeners for their favorite albums of 2017

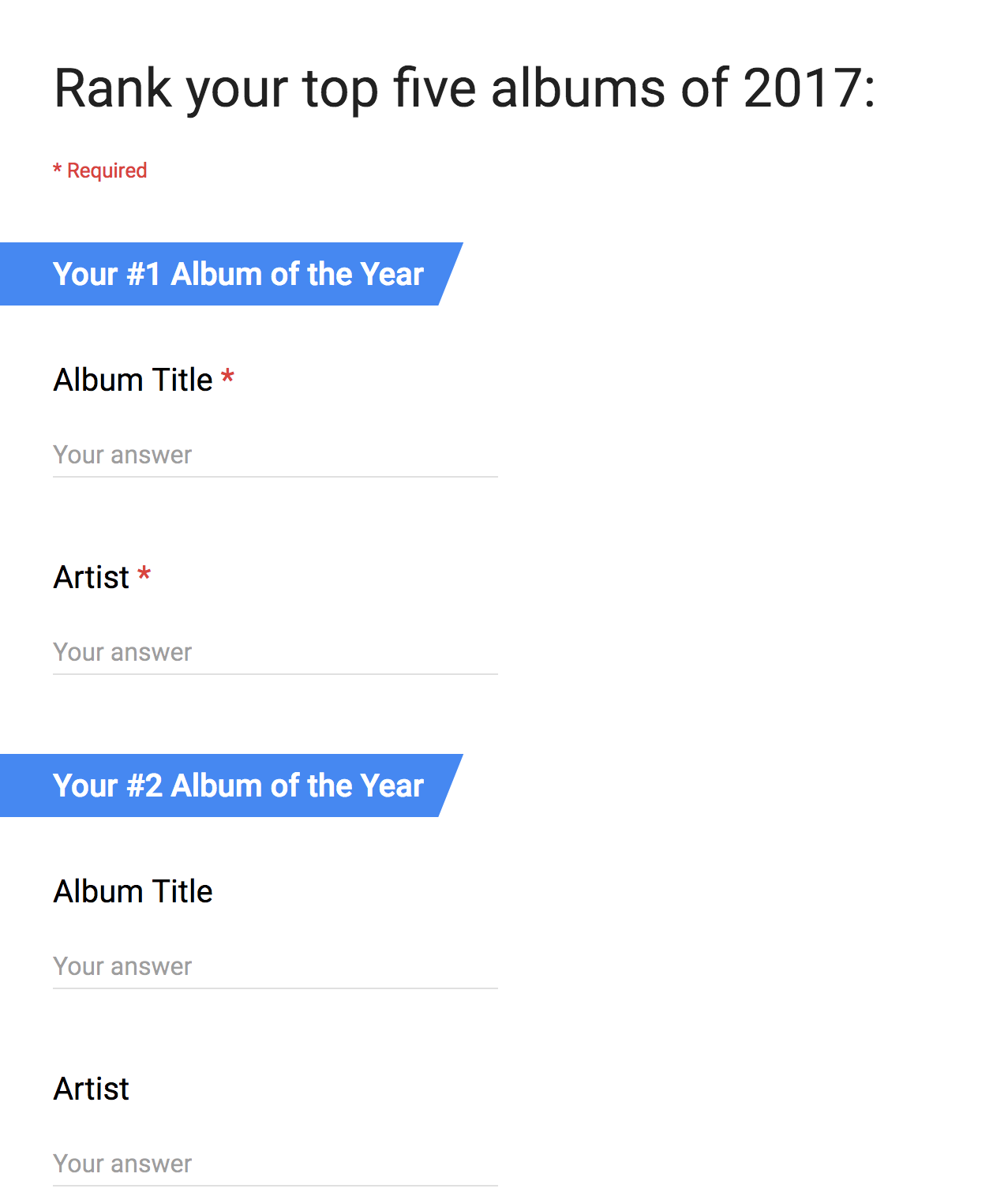

As 2017 was coming to an end, All Songs Considered continued a longstanding tradition and asked listeners for their favorite albums of 2017. Users could enter up to five different albums and artist pairs in a Google Form, ranked according to their preferences. The poll was open for eight days and resulted in more than 4,800 entries.

In the end, the All Songs Considered team wanted a ranked list of the best albums. We already dove into this task in 2016, and you can check the process in this old post. However, after reviewing code snippets from last year we decided to take a new approach this year. In this post we will explain the decisions we made and why we think it is an improvement that will allow us to move forward more quickly in coming years.

Our main goals this year were:

- Improve the submission form to start with a cleaner dataset.

- Use a more programmatic approach to cluster similar entries for artist/album pairs.

- Use

maketo tie together our data processing pipeline. We were inspired by the awesome explanations of the use of Makefiles for data processing by Datamade. - Reuse ranking strategy from the previous year.

Let’s dive into each of those goals and how we tackled them.

Form improvements

Our first question was “is there a way to improve the audience submission Google form to provide cleaner initial results?” In previous years we had asked our audience to add a comma-separated artist and album pair, but that rule was not always followed. Surprise! Welcome to the world of free text fields.

This year we made two major changes. First, we decided to split album and artist into separate inputs grouped under a common heading. Second, we made the #1 album and artist fields required.

2017 form

2017 form

Looking back to that decision, it made a huge difference in the cleanliness of the original dataset. The separation of album and artist gave us a consistent data format and the required fields eliminated completely empty rows. It was useful to have a better starting point for our cleanup process.

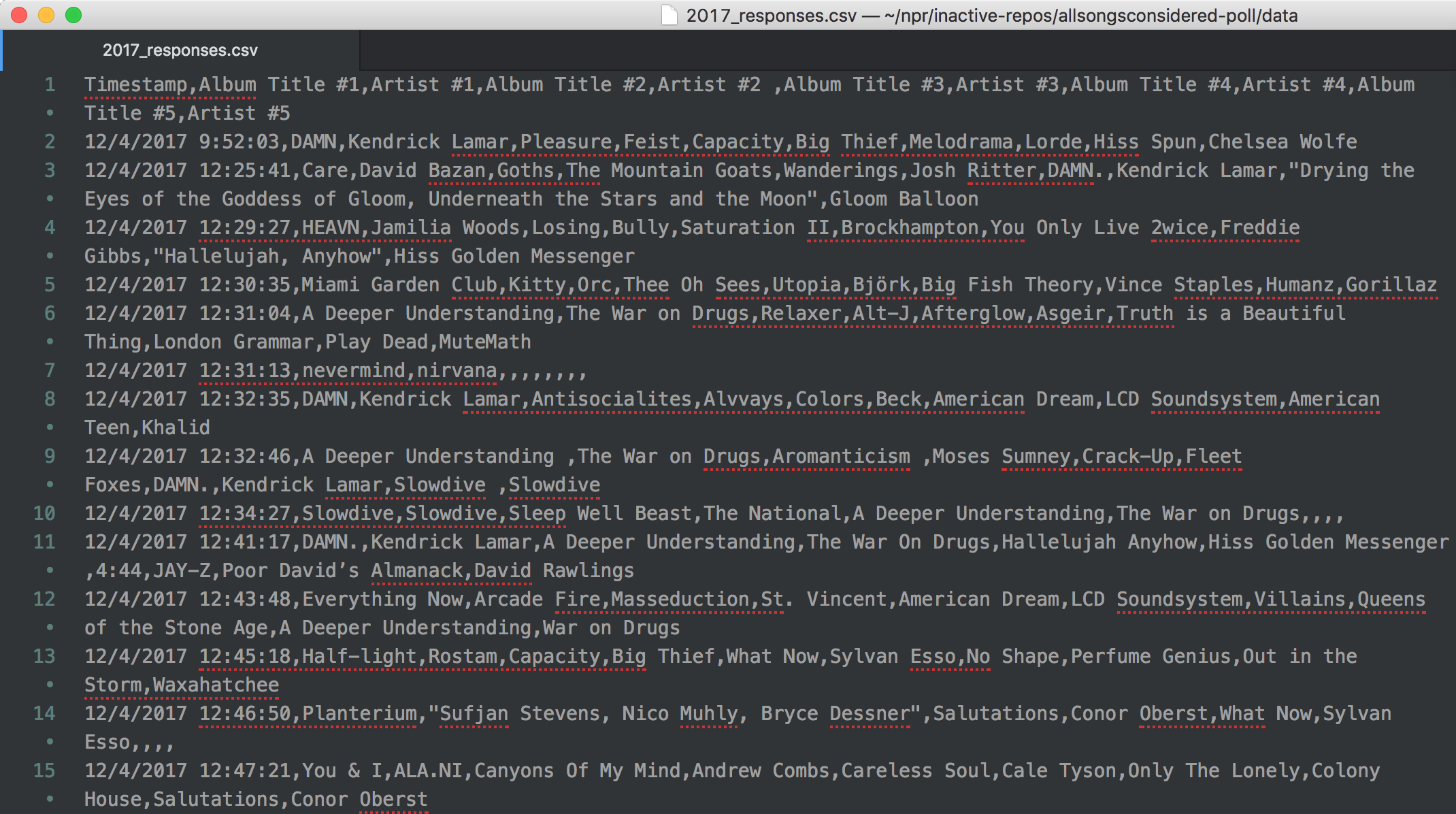

Original export of the 2017 form

Original export of the 2017 form

Clustering similar artist/album entries

Members of our team had already tried out dedupe in other projects and we thought this data cleaning task was well suited for that tool. We want to identify and group together similar artist/album pairs in order to correctly rank them later.

We finally used csvdedupe, a command line tool for deduplicating CSV files, that takes a messy input file or data piped from standard input and identifies duplicates.

Installation is as easy as using pip:

pip install csvdedupe

Preparing data for csvdedupe

In order to use csvdedupe effectively, we first needed to change the format of the input data so that every artist/album pair was in a different row. That way csvdedupe could work across all of the entries and group them.

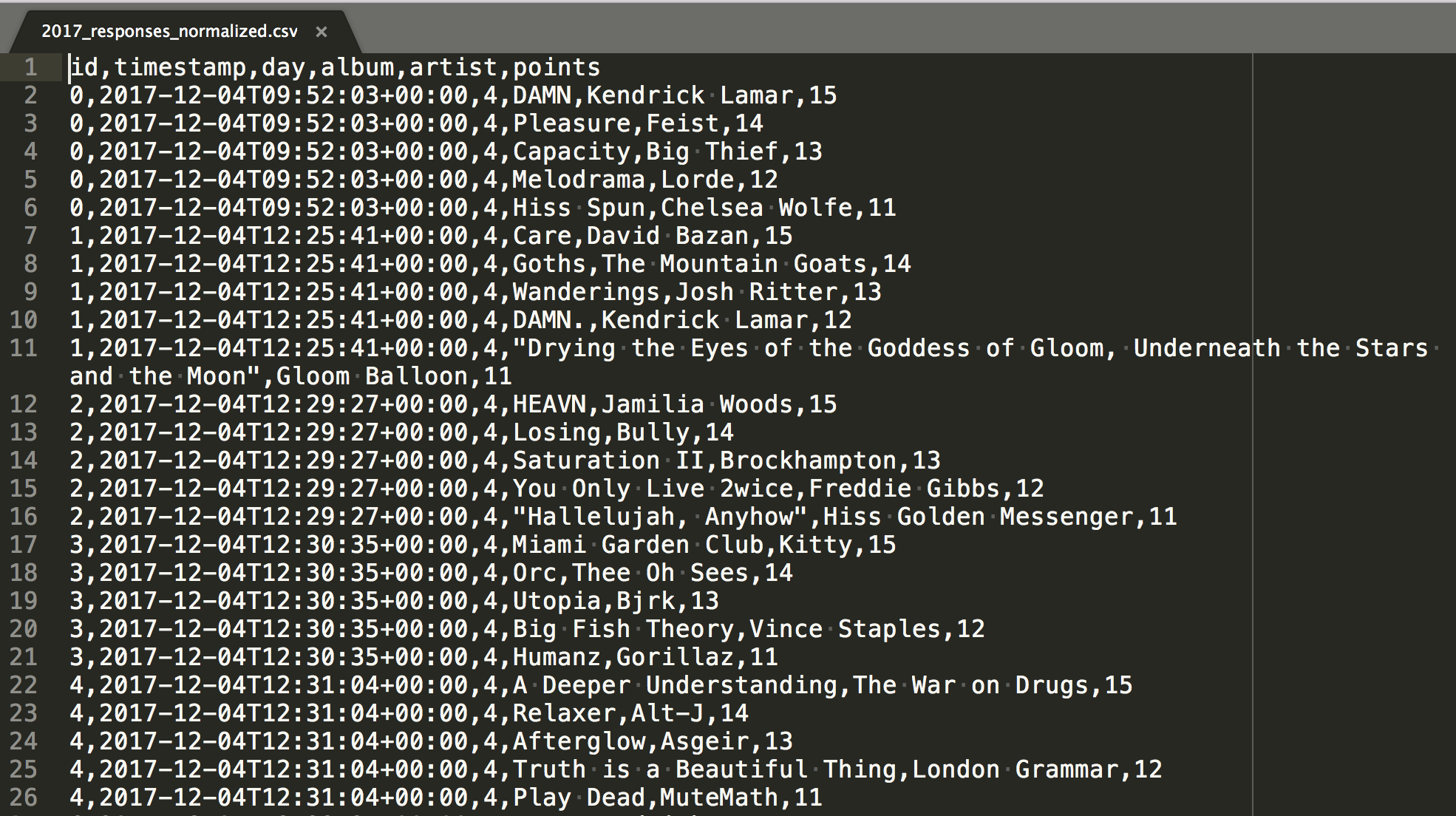

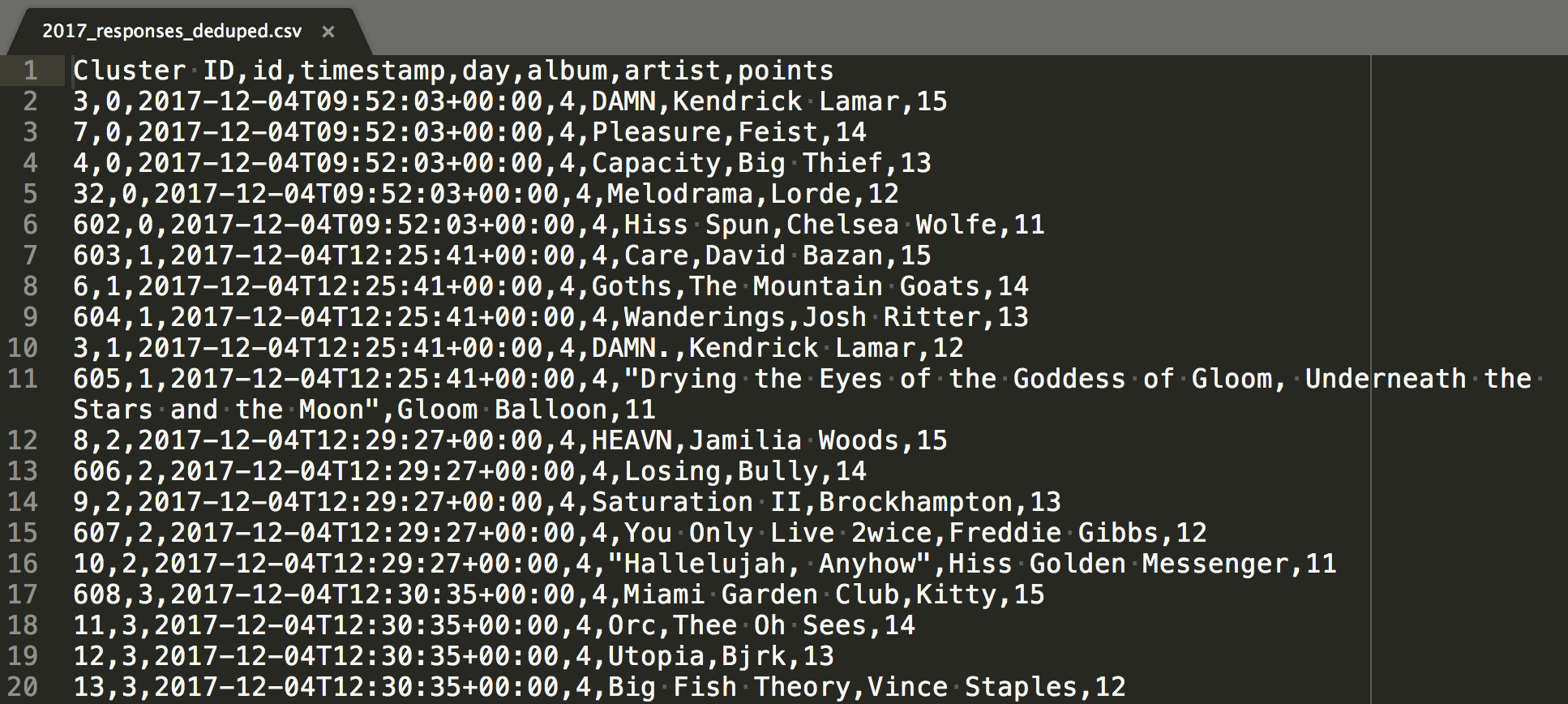

One artist/album pair per row

One artist/album pair per row

As you can see in the above CSV output, we have assigned points to each album/artist pair depending on the position in the Google form. We wanted a point schema that would always rank two votes for an artist/album pair higher than a single vote, regardless of the single vote’s position.

So in order to comply with the above rule, we have assigned points like this:

- 15 points to album/artist #1

- 14 points to album/artist #2

- 13 points to album/artist #3

- 12 points to album/artist #4

- 11 points to album/artist #5

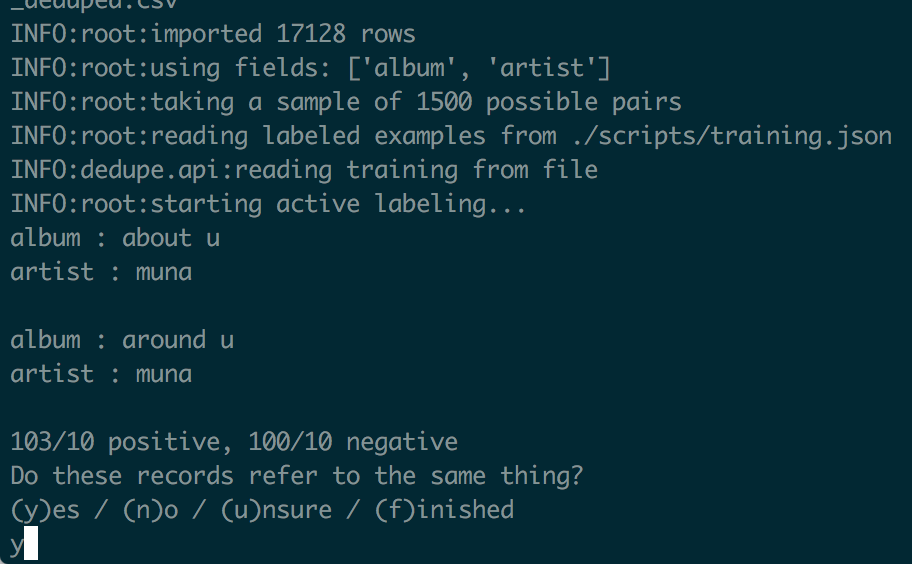

Training csvdedupe

Dedupe uses a supervised machine learning algorithm to detect what we want to identify as similar. The first step in using it is training the algorithm. Dedupe suggests that we provide at least 10 positive results (similar entries) and 10 negative results (dissimilar entries) for it to build a model that can give us accurate results.

Training dedupe on the terminal

Training dedupe on the terminal

Verifying csvdedupe results

Dedupe was a huge improvement in terms of simplifying our detection of similar entries, but we wanted some kind of manual verification step to fine tune entries that were either bundled together incorrectly or not bundled together when they should have been.

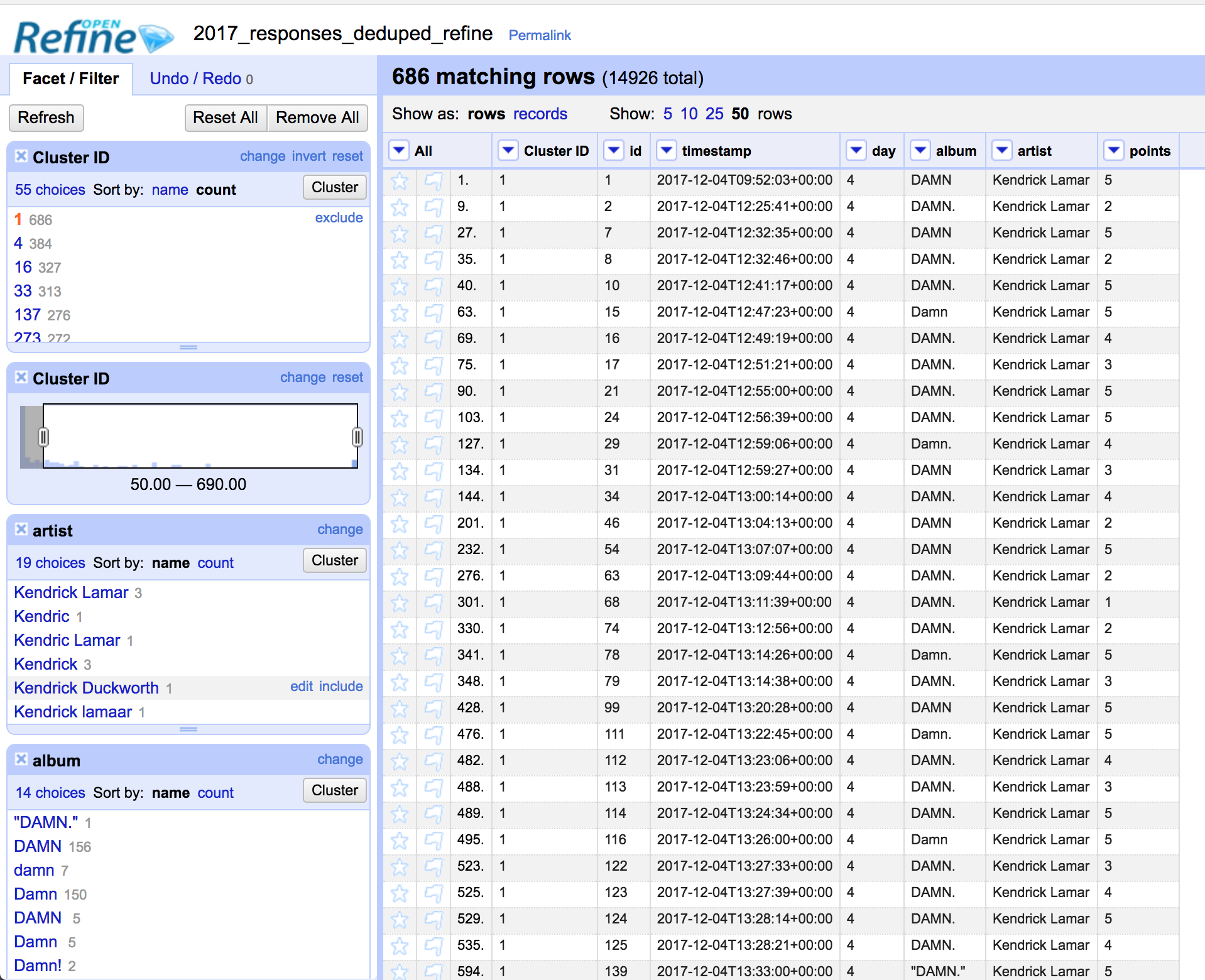

For this we used OpenRefine. With its visual faceting capabilities it allows you to quickly identify the most prominent clusters and review them to search for incongruencies.

Using facets on OpenRefine to verify dedupe results

Using facets on OpenRefine to verify dedupe results

Using makefiles for our data processing pipeline

As Mike Bostock, the creator of D3.js, states in this article - “Makefiles are machine-readable documentation that make your workflow reproducible”.

It takes a while to adapt yourself to the syntax of a makefile, but once you start to get familiar with it, you start to move more quickly and at the end you will have a reproducible data pipeline. Your teammates or your future self will be really happy that you spent the time to document the process in a makefile when they need to reproduce the workflow on a tight deadline.

Basic Syntax

A makefile is a set of rules with the following format:

targetfile: sourcefile(s)

command(s)

targetfileis the file you want to generate.sourcefile(s)are the file(s) it depends on.command(s)is what you need to run in a shell to generate the target file.

You can then chain these rules, making the next rule’s sourcefile the targetfile of a previous rule. In that way you generate a pipeline through which your data flows.

Let’s see an example from our own makefile

INPUT_DATA_DIR = data

INPUT_FILE = 2017_responses.csv

OUTPUT_DATA_DIR = output

...

# clean and dedupe rules

clean_dedupe: $(OUTPUT_DATA_DIR)/2017_responses_deduped.csv

$(OUTPUT_DATA_DIR)/2017_responses_deduped.csv: $(OUTPUT_DATA_DIR)/2017_responses_normalized.csv

./scripts/dedupe.sh $< > $@

$(OUTPUT_DATA_DIR)/2017_responses_normalized.csv: $(INPUT_DATA_DIR)/$(INPUT_FILE) $(OUTPUT_DATA_DIR)

cat $< | ./scripts/clean_ballot_stuffing.py | ./scripts/transform_form_responses.py > $@

...

# Aux rules

$(OUTPUT_DATA_DIR):

mkdir -p $(OUTPUT_DATA_DIR)

...

At first, looking at the rules can be overwhelming, but let us walk you through what they actually do. Trust me, in no time you’ll fall in love with the approach.

Defining variables

You can define variables in your makefiles, for example OUTPUT_DATA_DIR in the snippet above, and you can then refer to them in your rules in this way: $(OUTPUT_DATA_DIR).

Automatic variables

GNU make comes with some automatic variables that you can use in your recipe to refer to specific target or source files:

$@- the filename of the target$^- the filenames of all dependencies$?- the filenames of all dependencies that are newer than the target$<- the filenames of the first dependency

In our example we are using $< as the input to a given command and $@ as the destination for the output of the command.

Using Makefile chain syntax

We run make clean_dedupe to execute our cleaning and dedupe pipeline.

You can see that is one of our targetfiles in the Makefile, but it has a dependency on a file in the filesystem. If the dependency of the specified target does not exist or needs to be regenerated since one of its dependencies has changed, make will also build those dependencies.

make will find another rule whose targetfile matches the filename in the previous rule and will, in turn, search for any dependencies it needs to build in order to generate the target.

Can you start to see the chain behavior?

Understanding the make recipes

The example makefile shown above could be translated to the following initial execution:

cat data/2017_responses.csv | ./scripts/clean_ballot_stuffing.py | ./scripts/transform_form_responses.py > output/2017_responses_normalized.csv- Start with the raw form responses.

- Use a Python script to remove duplicate entries in a given time window.

- Use another Python script to transform the responses into one artist/album pair per row and assign points to each entry.

-

./scripts/dedupe.sh output/2017_responses_normalized.csv > output/2017_responses_deduped.csv- Train

csvdedupeand then apply the machine learned algorithm to cluster similar entries together. - Dump the output to a CSV file named

output/2017_responses_deduped.csv.

- Train

Dedupe output with Cluster IDs

Dedupe output with Cluster IDs

Suggestions when using makefiles

In order to take full advantage of the makefile approach here are some suggestions:

- Always try to use

stdinandstdoutas input and output for your helper scripts so that you can pipe scripts together. - Think backwards: Start with the final output rule and then start to write the rules that will need to generate its dependencies.

- Use automatic variables to avoid hardcoding filenames on your commands.

Reuse 2016 ranking strategy

Even though our approach to data cleaning was quite different from 2016, once the data was cleaned we reused the ranking strategy to provide consistency with the previous year’s Top 100 list.

Lisa, who did the analysis in 2016, liked to work in R and we like to work in Python so we reimplemented her strategy by relying on the pandas library.

Code

Do you want to take a look at the full Makefile or look at the process we used to rank the entries to arrive at the Top 100? Take a look at our repo.

The final ranking is published on All Songs Considered.

visuals + editorial graphics

visuals + editorial graphics