How we work

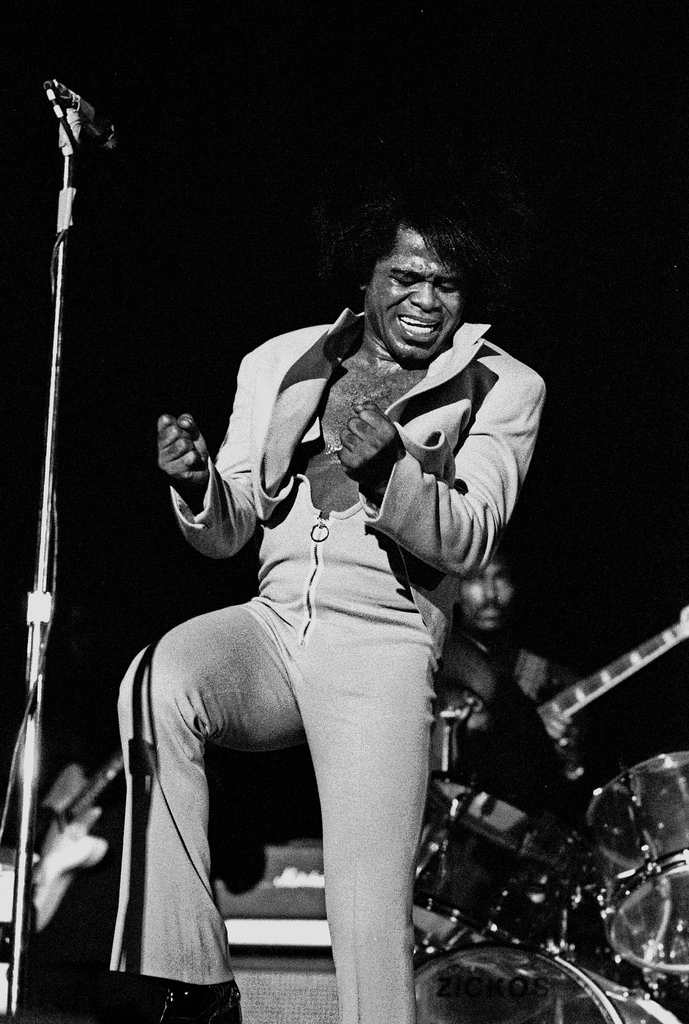

Geballte Energie: James Brown, Februar 1973, Musikhalle Hamburg by Heinrich Klaffs

We wrote this for the newsroom. It’s changed some since we first distributed it internally, and, like our other processes, will change much more as we learn by doing.

Process must never be a burden, and never be static. If we’re doing it right, the way we work should feel lighter and easier every week. (I’ve edited/annotated it a tiny bit to make sense as a blog post, but didn’t remove any sekrits.)

How we got here

The visuals team was assembled at the end of last year. We’re the product of merging two groups: the news applications team, who served as NPR’s graphics and data desks, and the multimedia team, who made and edited pictures and video.

Our teams were already both making visual news things, often in collaboration. When the leader of the multimedia team left NPR last fall, we all did a lot of soul searching. And we realized that we had a lot to learn from each other.

The multimedia crew wanted to make pictures and video that were truly web-native, which required web makers. And our news apps lacked empathy — something we’re so great at on the radio. It’s hard to make people care with a chart. Pictures were the obvious missing piece. We needed each other.

In addition, it seemed that we would have a lot to gain by establishing a common set of priorities. So we decided to get the teams together. The working titles for the new team — “We make people care” and “Good Internet” — reflected our new shared vision. But in the end, we settled on a simple name, “Visuals”.

(See also: “What is your mission?”, a post published on my personal blog, because swears.)

Our role in the newsroom

Everything we do is driven by the priorities of the newsroom, in collaboration with reporters and editors. We don’t want to go it alone. We’d be dim if we launched a project about the Supreme Court and didn’t work with Nina Totenberg.

Here’s the metaphor I’ve been trying out on reporters and editors:

We want to be your rhythm section. But that’s not to say we’re not stars. We want to be the best rhythm section. We want to be James Brown’s rhythm section. But we’re not James. We’re gonna kick ass and make you look good, but we still need you to write the songs. And we play together.

Our priorities

We love making stuff, but we can’t possibly do every project that crosses our desks. So we do our best to prioritize our work, and our top priority is serving NPR’s audience.

We start every project with a user-centered design exercise. We talk about our users, their needs, and then discuss the features we might build. And often the output of that exercise is not a fancy project.

(This process is a great mind-hack. We all get excited about a cool new thing, but most of the time the cool new thing is not the right thing to build for our audience. User-centered design is an exercise in self-control.)

Sometimes we realize the best thing to publish is a list post, or a simple chart alongside a story, or a call-to-action on Facebook — that is to say, something we don’t make. But sometimes we do need to build something, and put it on the schedule.

We make…

- Photographs and video for enterprise news stories

- Charts, maps, and other daily news graphics

- Data-driven news applications and visualizations

- Visual, web-native stories

And we…

- Edit images from wire services and social media for use with daily news stories

- Assign freelancers to illustrate stories

- Train and edit NPR reporters when they make pictures for their stories

- Work with editors to create visual strategies for their coverage

- Design and deploy social media projects like Tumblr blogs

- Write and edit The Picture Show blog

- Create tools and conduct training for the newsroom

Team structure

Visual journalism experts. David Sweeney/NPR.

There are twelve of us (soon to be thirteen!) on the visuals team, and we’re still learning the most effective ways to work together. The following breakdown is an ongoing experiment.

Two people dedicated to daily news photography

We currently have one full-time teammate, Emily Bogle, working on pictures for daily news, and we are in the process of hiring another. They attend news meetings and are available to help the desks and shows with short-term visuals.

If you need a photo, go to Emily.

One person dedicated to daily news graphics

Similarly, our graphics editor, Alyson Hurt, is our primary point of contact when you need graphics for daily and short-term stories. She is also charged with maintaining design standards for news graphics on npr.org, ensuring quality and consistency.

If you need a graphic created, go to Aly.

If you are making your own graphic, go to Aly.

If you are planning to publish somebody else’s graphic, go to Aly.

Two lead editors

Brian Boyer and Kainaz Amaria serve as NPR’s visuals editor and pictures editor, respectively. Sometimes they make things, but their primary job is to act as point on project requests, decide what we will and won’t do, serve as primary stakeholders on projects, and define priorities and strategy for the team.

If you’ve got a project, go to Brian or Kainaz, ASAP.

One photojournalist

We’ve got one full-time photographer/videographer, David Gilkey, who work with desks and shows to make visuals for our online storytelling.

Five makers and two managers on project teams

The rest of the crew rotates between two project teams (usually three or four people) each run by a project manager. Folks rotate between teams, and sometimes rotate onto daily news work, depending on the needs of the project and the newsroom.

This work is generally planned. These are the format-breakers — data-driven applications or visual stories. The projects range from 1-week to 6-weeks in duration (usually around 2-3 weeks).

And since we’re reorganizing, some other things we’re gonna try

We’re taking this opportunity to rethink some of our processes and how we work with the newsroom, including…

Very short, monthly meetings with each desk and show

Until recently, our only scheduled weekly catchup was with Morning Edition. And, no surprise, we’ve ended up doing a lot of work with them. A couple of months ago, we started meeting with each desk and show, once a month. It’s not a big meeting, just a couple of folks from each team. And it’s only for 15 minutes — just enough time to catch up on upcoming stories.

Fewer photo galleries, more photo stories

Photo galleries are nice, but when we’ve sent a photographer to far-off lands, it just doesn’t make sense to place their work at the top of a written story, buried under a click, click, click user interface. When we’ve got the art, we want to use it, boldly.

More self-service tools

We like making graphics, but there’s always more to do then we are staffed to handle. And too often a graphic requires such a short turn-around that we’re just not able to get to them. We’d love to know about your graphics needs as soon as possible, but when that’s not possible, we’ve got tools to make some graphics self-serve.

(I wanted to link to these tools, but they’re internal, and we haven’t blogged about them yet. Shameful! Here’s some source code: Chartbuilder, Quotable, Papertrail)

Slow news

For breaking news events and time-sensitive stories, we’ll do what we’ve been doing — we’ll time our launches to coincide with our news stories.

But the rest of the time, we’re going to try something new. It seems to us that running a buildout and a visual story on the same day is a mistake. It’s usually an editing headache to launch two different pieces at the same time. And then once you’ve launched, the pieces end up competing for attention on the homepage and social media. It’s counter-productive.

So instead, we’re going to launch after the air date and buildout, as a second- or third-day story.

This “slow news” strategy may work at other organizations, but it seems to make extra sense at NPR since so much of our work is explanatory, and evergreen. Also, visuals usually works on stories that are of extra importance to our audience, so a second-day launch will give us an opportunity to raise an important issue a second time.

visuals + editorial graphics

visuals + editorial graphics